Abstraction is a technique for dealing with complexity. It works by establishing a level of complexity we are interested in, and suppressing the more complex details below that level.

The guiding principle of abstraction is that only details that are relevant to the current perspective or the task at hand need to be considered. As most programs are written to solve complex problems involving large amounts of intricate details, it is impossible to deal with all these details at the same time. That is where abstraction can help.

Data abstraction: abstracting away the lower level data items and thinking in terms of bigger entities

Within a certain software component, you might deal with a user data type, while ignoring the details contained in the user data item such as name, and date of birth. These details have been ‘abstracted away’ as they do not affect the task of that software component.

Control abstraction: abstracting away details of the actual control flow to focus on tasks at a higher level

print(“Hello”) is an abstraction of the actual output mechanism within the computer.

Abstraction can be applied repeatedly to obtain progressively higher levels of abstraction.

An example of different levels of data abstraction: a File is a data item that is at a higher level than an array and an array is at a higher level than a bit.

An example of different levels of control abstraction: execute(Game) is at a higher level than print(Char) which is at a higher level than an Assembly language instruction MOV.

Abstraction is a general concept that is not limited to just data or control abstractions.

Some more general examples of abstraction:

- An OOP class is an abstraction over related data and behaviors.

- An architecture is a higher-level abstraction of the design of a software.

- Models (e.g., UML models) are abstractions of some aspect of reality.

Coupling is a measure of the degree of dependence between components, classes, methods, etc. Low coupling indicates that a component is less dependent on other components. High coupling (aka tight coupling or strong coupling) is discouraged due to the following disadvantages:

- Maintenance is harder because a change in one module could cause changes in other modules coupled to it (i.e. a ripple effect).

- Integration is harder because multiple components coupled with each other have to be integrated at the same time.

- Testing and reuse of the module is harder due to its dependence on other modules.

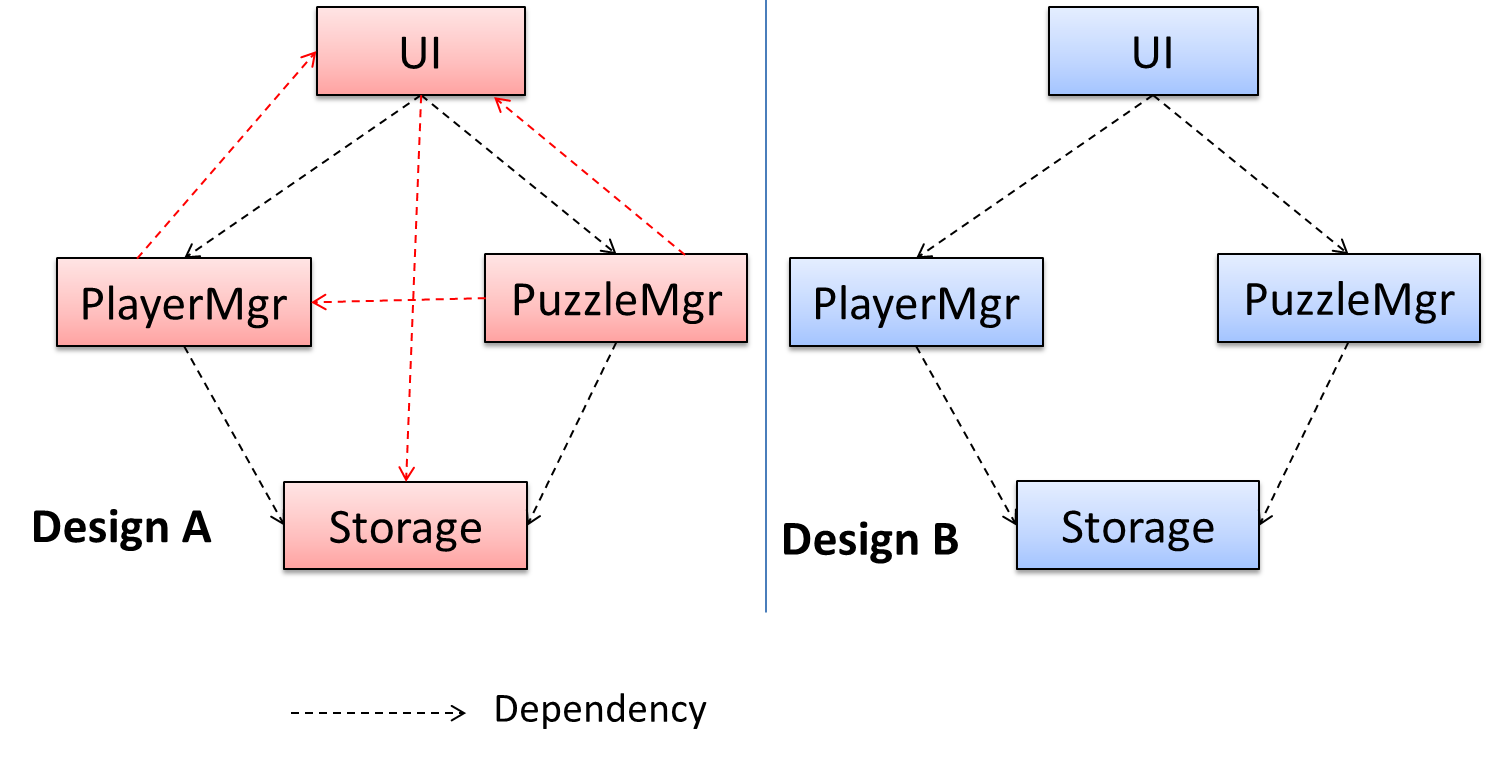

In the example below, design A appears to have more coupling between the components than design B.

Exercises

X is coupled to Y if a change to Y can potentially require a change in X.

If the Foo class calls the method Bar#read(), Foo is coupled to Bar because a change to Bar can potentially (but not always) require a change in the Foo class e.g. if the signature of Bar#read() is changed, Foo needs to change as well, but a change to the Bar#write() method may not require a change in the Foo class because Foo does not call Bar#write().

code for the above example

Some examples of coupling: A is coupled to B if,

Ahas access to the internal structure ofB(this results in a very high level of coupling)AandBdepend on the same global variableAcallsBAreceives an object ofBas a parameter or a return valueAinherits fromBAandBare required to follow the same data format or communication protocol

Exercises

Some examples of different coupling types:

- Content coupling: one module modifies or relies on the internal workings of another module e.g., accessing local data of another module

- Common/Global coupling: two modules share the same global data

- Control coupling: one module controlling the flow of another, by passing it information on what to do e.g., passing a flag

- Data coupling: one module sharing data with another module e.g. via passing parameters

- External coupling: two modules share an externally imposed convention e.g., data formats, communication protocols, device interfaces.

- Subclass coupling: a class inherits from another class. Note that a child class is coupled to the parent class but not the other way around.

- Temporal coupling: two actions are bundled together just because they happen to occur at the same time e.g. extracting a contiguous block of code as a method although the code block contains statements unrelated to each other

Cohesion is a measure of how strongly-related and focused the various responsibilities of a component are. A highly-cohesive component keeps related functionalities together while keeping out all other unrelated things.

Higher cohesion is better. Disadvantages of low cohesion (aka weak cohesion):

- Lowers the understandability of modules as it is difficult to express module functionalities at a higher level.

- Lowers maintainability because a module can be modified due to unrelated causes (reason: the module contains code unrelated to each other) or many modules may need to be modified to achieve a small change in behavior (reason: because the code related to that change is not localized to a single module).

- Lowers reusability of modules because they do not represent logical units of functionality.

Cohesion can be present in many forms. Some examples:

- Code related to a single concept is kept together, e.g. the

Studentcomponent handles everything related to students. - Code that is invoked close together in time is kept together, e.g. all code related to initializing the system is kept together.

- Code that manipulates the same data structure is kept together, e.g. the

GameArchivecomponent handles everything related to the storage and retrieval of game sessions.

Suppose a Payroll application contains a class that deals with writing data to the database. If the class includes some code to show an error dialog to the user if the database is unreachable, that class is not cohesive because it seems to be interacting with the user as well as the database.

Exercises