What

Software development goes through different stages such as requirements, analysis, design, implementation and testing. These stages are collectively known as the software development life cycle (SDLC). There are several approaches, known as software development life cycle models (also called software process models), that describe different ways to go through the SDLC. Each process model prescribes a "roadmap" for the software developers to manage the development effort. The roadmap describes the aims of the development stage(s), the artifacts or outcome of each stage, as well as the workflow i.e. the relationship between stages.

Sequential Models

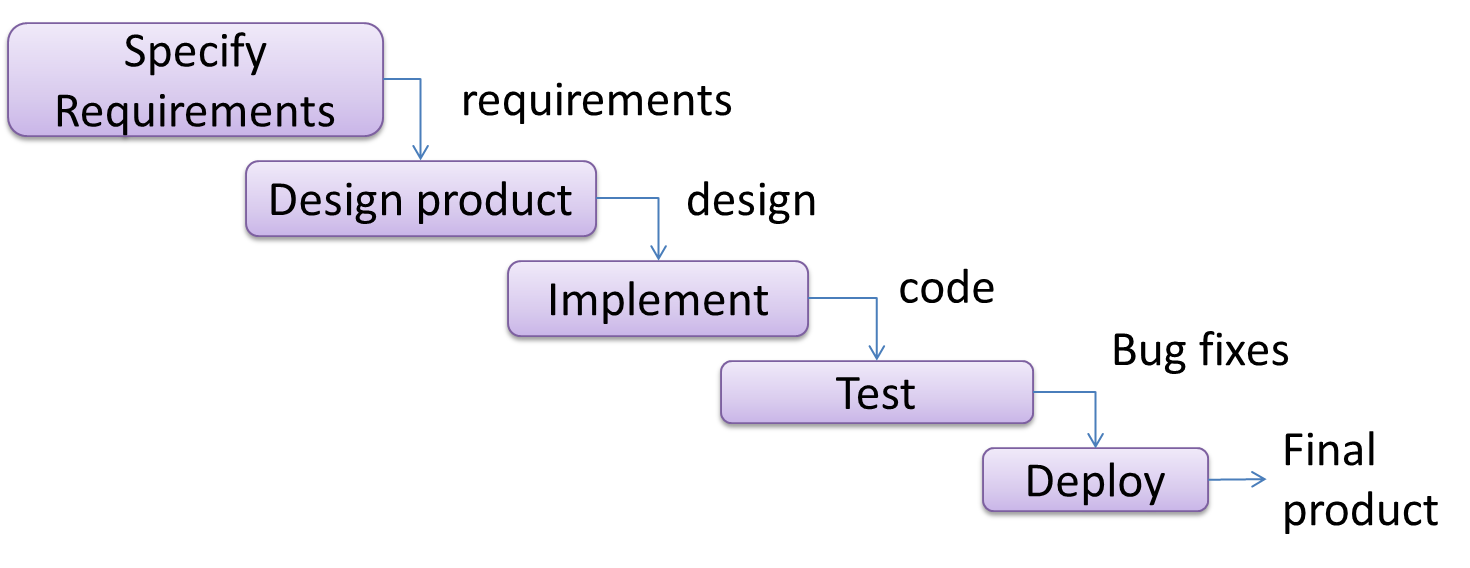

The sequential model, also called the waterfall model, models software development as a linear process, in which the project is seen as progressing steadily in one direction through the development stages. The name waterfall stems from how the model is drawn to look like a waterfall (see below).

When one stage of the process is completed, it should produce some artifacts to be used in the next stage. For example, upon completion of the requirements stage, a comprehensive list of requirements is produced that will see no further modifications. A strict application of the sequential model would require each stage to be completed before starting the next.

This could be a useful model when the problem statement is well-understood and stable. In such cases, using the sequential model should result in a timely and systematic development effort, provided that all goes well. As each stage has a well-defined outcome, the progress of the project can be tracked with relative ease.

The major problem with this model is that the requirements of a real-world project are rarely well-understood at the beginning and keep changing over time. One reason for this is that users are generally not aware of how a software application can be used without prior experience in using a similar application.

Iterative Models

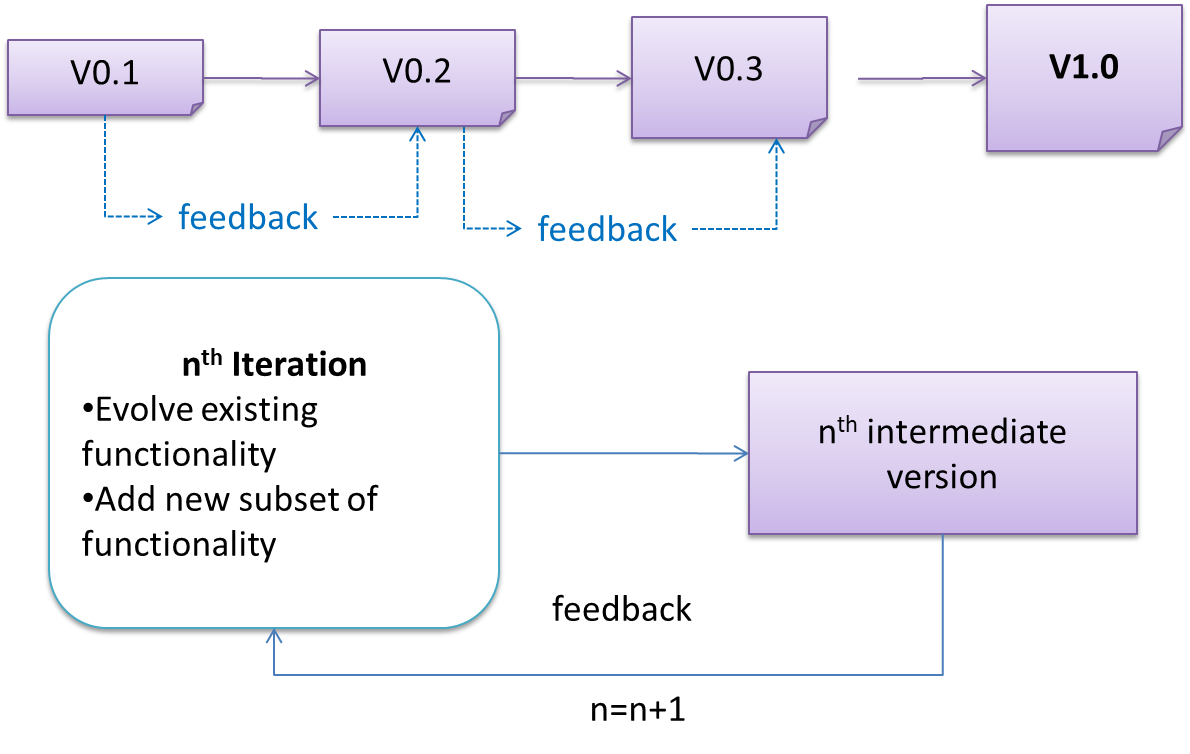

The iterative model (sometimes called iterative and incremental) advocates having several iterations of SDLC. Each of the iterations could potentially go through all the development stages, from requirements gathering to testing & deployment. Roughly, it appears to be similar to several cycles of the sequential model.

In this model, each of the iterations produces a new version of the product. Feedback on the new version can then be fed to the next iteration. Taking the Minesweeper game as an example, the iterative model will deliver a fully playable version from the early iterations. However, the first iteration will have primitive functionality, for example, a clumsy text based UI, fixed board size, limited randomization, etc. These functionalities will then be improved in later releases.

The iterative model can take a breadth-first or a depth-first approach to iteration planning.

- breadth-first: an iteration evolves all major components in parallel e.g., add a new feature fully, or enhance an existing feature.

- depth-first: an iteration focuses on fleshing out only some components e.g., update the backend to support a new feature that will be added in a future iteration.

Most projects use a mixture of breadth-first and depth-first iterations i.e., an iteration can contain some breadth-first work as well as some depth-first work.

Agile Models

In 2001, a group of prominent software engineering practitioners met and brainstormed for an alternative to documentation-driven, heavyweight software development processes that were used in most large projects at the time. This resulted in something called the agile manifesto (a vision statement of what they were looking to do).

You are uncovering better ways of developing software by doing it and helping others do it.

Through this work you have come to value:

- Individuals and interactions over processes and tools

- Working software over comprehensive documentation

- Customer collaboration over contract negotiation

- Responding to change over following a plan

That is, while there is value in the items on the right, you value the items on the left more.

-- Extract from the Agile Manifesto

Subsequently, some of the signatories of the manifesto went on to create process models that try to follow it. These processes are collectively called agile processes. Some of the key features of agile approaches are:

- Requirements are prioritized based on the needs of the user, are clarified regularly (at times almost on a daily basis) with the entire project team, and are factored into the development schedule as appropriate.

- Instead of doing a very elaborate and detailed design and a project plan for the whole project, the team works based on a rough project plan and a high level design that evolves as the project goes on.

- There is a strong emphasis on complete transparency and responsibility sharing among the team members. The team is responsible together for the delivery of the product. Team members are accountable, and regularly and openly share progress with each other and with the user.

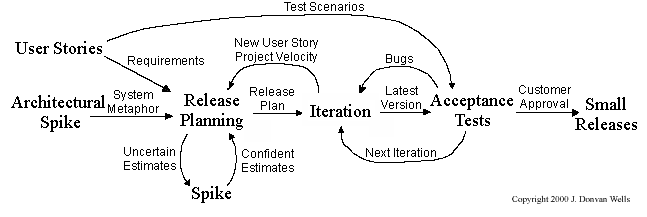

There are a number of agile processes in the development world today. eXtreme Programming (XP) and Scrum are two of the well-known ones.

XP

The following description was adapted from the XP home page, emphasis added:

Extreme Programming (XP) stresses customer satisfaction. Instead of delivering everything you could possibly want on some date far in the future, this process delivers the software you need as you need it.

XP aims to empower developers to confidently respond to changing customer requirements, even late in the life cycle.

XP emphasizes teamwork. Managers, customers, and developers are all equal partners in a collaborative team. XP implements a simple, yet effective environment enabling teams to become highly productive. The team self-organizes around the problem to solve it as efficiently as possible.

XP aims to improve a software project in five essential ways: communication, simplicity, feedback, respect, and courage. Extreme Programmers constantly communicate with their customers and fellow programmers. They keep their design simple and clean. They get feedback by testing their software starting on day one. Every small success deepens their respect for the unique contributions of each and every team member. With this foundation, Extreme Programmers are able to courageously respond to changing requirements and technology.

XP has a set of simple rules. XP is a lot like a jig saw puzzle with many small pieces. Individually the pieces make no sense, but when combined together a complete picture can be seen. This flow chart shows how Extreme Programming's rules work together.

Pair programming, CRC cards, project velocity, and standup meetings are some interesting topics related to XP. Refer to extremeprogramming.org to find out more about XP.

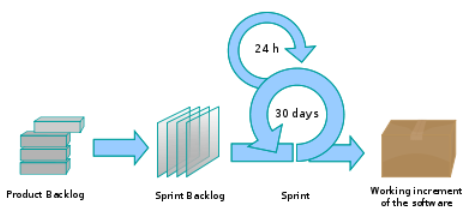

Scrum

This description of Scrum was adapted from Wikipedia [retrieved on 18/10/2011], emphasis added:

Scrum is a process skeleton that contains sets of practices and predefined roles. The main roles in Scrum are:

- The Scrum Master, who maintains the processes (typically in lieu of a project manager)

- The Product Owner, who represents the stakeholders and the business

- The Team, a cross-functional group who do the actual analysis, design, implementation, testing, etc.

A Scrum project is divided into iterations called Sprints. A sprint is the basic unit of development in Scrum. Sprints tend to last between one week and one month, and are a timeboxed (i.e. restricted to a specific duration) effort of a constant length.

Each sprint is preceded by a planning meeting, where the tasks for the sprint are identified and an estimated commitment for the sprint goal is made, and followed by a review or retrospective meeting, where the progress is reviewed and lessons for the next sprint are identified.

During each sprint, the team creates a potentially deliverable product increment (for example, working and tested software). The set of features that go into a sprint come from the product backlog, which is a prioritized set of high level requirements of work to be done. Which backlog items go into the sprint is determined during the sprint planning meeting. During this meeting, the Product Owner informs the team of the items in the product backlog that he or she wants completed. The team then determines how much of this they can commit to complete during the next sprint, and records this in the sprint backlog. During a sprint, no one is allowed to change the sprint backlog, which means that the requirements are frozen for that sprint. Development is timeboxed such that the sprint must end on time; if requirements are not completed for any reason they are left out and returned to the product backlog. After a sprint is completed, the team demonstrates the use of the software.

Scrum enables the creation of self-organizing teams by encouraging co-location of all team members, and verbal communication between all team members and disciplines in the project.

A key principle of Scrum is its recognition that during a project the customers can change their minds about what they want and need (often called requirements churn), and that unpredicted challenges cannot be easily addressed in a traditional predictive or planned manner. As such, Scrum adopts an empirical approach—accepting that the problem cannot be fully understood or defined, focusing instead on maximizing the team’s ability to deliver quickly and respond to emerging requirements.

Daily Scrum is another key scrum practice. The description below was adapted from https://www.mountaingoatsoftware.com (emphasis added):

In Scrum, on each day of a sprint, the team holds a daily scrum meeting called the "daily scrum.” Meetings are typically held in the same location and at the same time each day. Ideally, a daily scrum meeting is held in the morning, as it helps set the context for the coming day's work. These scrum meetings are strictly time-boxed to 15 minutes. This keeps the discussion brisk but relevant.

...

During the daily scrum, each team member answers the following three questions:

- What did you do yesterday?

- What will you do today?

- Are there any impediments in your way?

...

The daily scrum meeting is not used as a problem-solving or issue resolution meeting. Issues that are raised are taken offline and usually dealt with by the relevant subgroup immediately after the meeting.